Read the full PDF version of the December 2025 More News here.

Give a Gift to TMI

We thank our generous donors for your continued support!

***Message français ci-dessous**

Every donation is a concrete gesture of support for better listening, more dialogue, and sharper curiosity!

ONLINE DONATIONS: Please follow this link: https://www.canadahelps.org/en/dn/2925

TELEPHONE DONATIONS: Please call our office at 1 (514) 935-9585.

FAX DONATIONS: Please fax your donation to 1 (514) 316-7406.

MAIL-IN DONATIONS: Please print and complete this form, and send to:

Thomas More Institute

3405 Atwater Avenue

Montréal, QC H3H 1Y2

**N.B. All cheques should be made payable to “The Thomas More Institute”**

LEGACY, BEQUESTS, AND SECURITIES DONATIONS: Please contact our Executive Director, Dina Souleiman, at d.souleiman@thomasmore.qc.ca for more details.

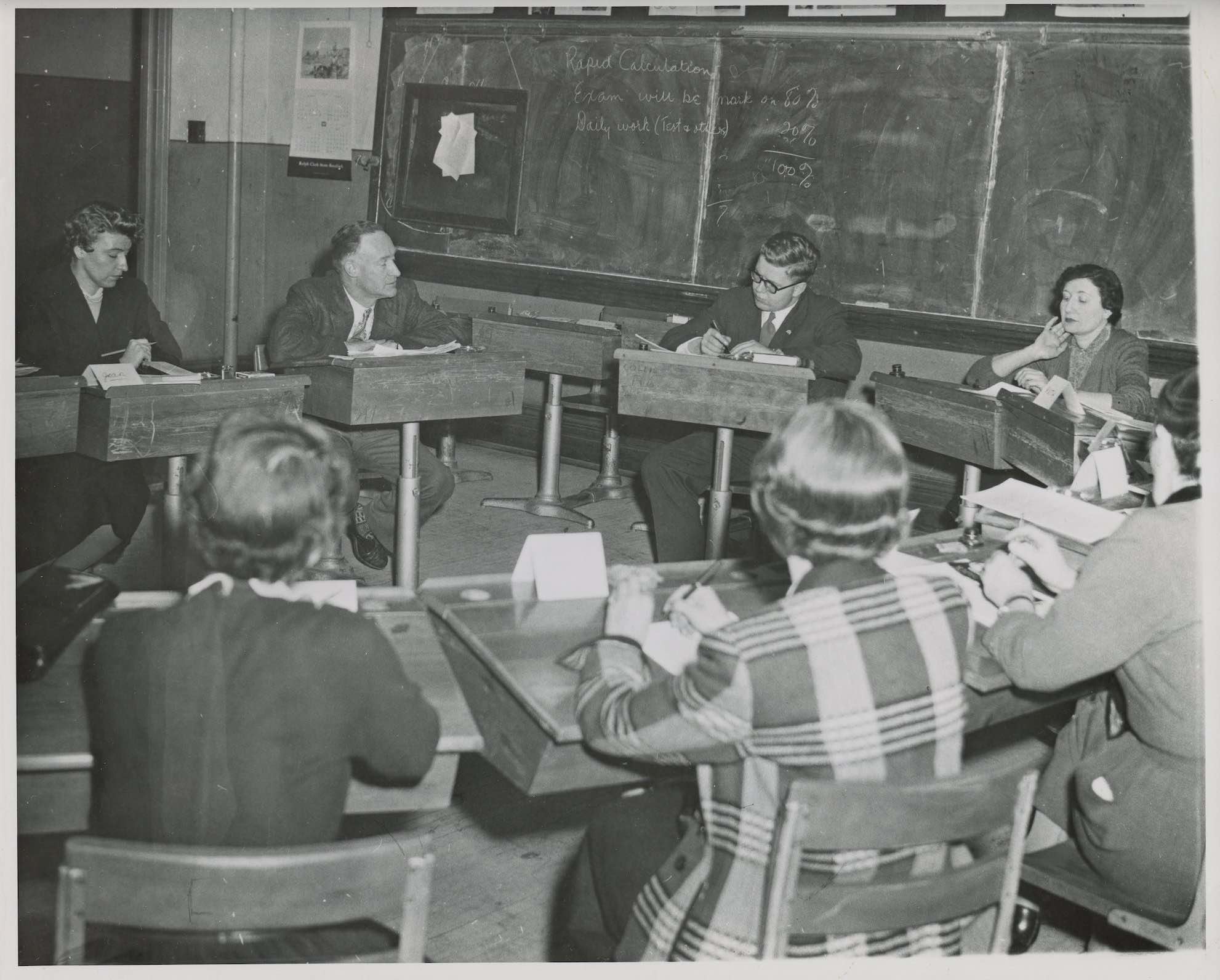

Mission

As a non-profit organization, TMI fosters and encourages lifelong education by creating and providing accessible university-level courses for adults of all ages. We practice a unique learning method that promotes discovery, freedom of expression, and intellectual growth within a collaborative space. The Institute aspires to provide a unique and vital place where ideas are exchanged, questions are pursued, and individuals are transformed as part of a supportive learning community. Your gifts help us to continue in our journey to privilege curiosity-driven learning in the Liberal Arts!

Nous remercions nos généreux donateurs pour leur soutien constant!

Chaque don est un geste concret de soutien favorisant une meilleure écoute, plus de dialogue et un développement de la curiosité!

LES DONS EN LIGNE : Cliquez sur ce lien pour donner à l’ITM : https://www.canadahelps.org/fr/dn/2925

LES DONS PAR TÉLÉPHONE : SVP appelez notre bureau au numéro 1 (514) 935-9585.

LES DONS PAR FAX : SVP faxez votre don au numéro 1 (514) 316-7406.

LES DONS PAR LA POSTE : SVP imprimez et remplissez ce formulaire et envoyez-le à cette adresse :

L’Institut Thomas More

3405 Avenue Atwater

Montréal, QC H3H 1Y2

**N.B. Tous les chèques doivent être payables à l’ordre de « L’Institut Thomas More » **

LES LEGS D’HERITAGE ET DONS DE TITRES : Veuillez contacter notre directrice générale, Dina Souleiman (d.souleiman@thomasmore.qc.ca), pour plus de détails.

Notre mission

L’ITM est une organisation à but non lucratif qui favorise et encourage l’éducation tout au long de la vie en créant et en fournissant des cours de niveau universitaire accessibles aux adultes de tous âges. Nous pratiquons une méthode d’apprentissage unique qui favorise la découverte, la liberté d’expression et la croissance intellectuelle dans un espace de collaboration. L’Institut aspire à fournir un lieu unique et vital pour les échanges d’idées, l’approfondissement des questions et la transformation des individus dans une communauté d’apprentissage coopératif. Vos dons nous aident à poursuivre notre voyage pour privilégier l’apprentissage par l’exercice de la curiosité dans le domaine des arts libéraux !